Blazor Considered Harmful

The allure of Blazor is strong. The promise of building web apps with C# instead of JavaScript is the fondest dream of .NET developers. However, Blazor is no silver bullet. While it is impressive in many aspects, its complexity, unconventional design decisions, and unexpected pitfalls can quickly turn development into a harrowing experience.

After my deep dive into Blazor, I can safely say that there are better alternatives out there. For example, combining MVC with HTMX helped me create a simpler, more straightforward, and equally powerful web app.

Blazor: complexity made flesh

Blazor sells itself as the ideal framework for creating rich, interactive web applications with C# instead of JavaScript. This is a powerful selling point that has many people excited about the concept. I too once believed in Blazor’s promises. Until I used it to build a non-trivial application.

Now that I know Blazor better than my own family, I genuinely can’t think of a single advantage Blazor has over other web frameworks. During development, I repeatedly discovered annoyances and footguns in the framework that make it an absolute pain to work with.

I now share these pitfalls with you in the hope that you will avoid falling into them.

Pessimistic re-rendering

Like most web frameworks, Razor components re-render whenever their parameters change. However, unlike most web frameworks, Blazor makes some bizarre decisions about when to re-render. Namely, Blazor doesn’t bother to check parameters with complex types for equality. Instead, whenever a Razor component is checking its parameters for changes, it takes the lazy way out and doesn’t even bother to compare complex type parameters! It always assumes they have changed! This is so ridiculously unintuitive that it caused me weeks of headaches as I tried to figure out where all my unnecessary re-renders were coming from.

One of the most common patterns in any web framework is running a side effect when certain component props (a.k.a. parameters) have changed. For example, let’s imagine you have a paginated table component in React, and you wanted to fetch data only when certain props changed. Here’s how you would implement that:

useEffect(() => {

await fetchData();

}, [filters, sortColumn, sortDescending, pageNumber, maxPages]);It’s at least somewhat straightforward. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying React’s approach to side effects is good, because it’s not. useEffect is undoubtedly a footgun in React, and it’s even been called React’s billion dollar problem. But at least it’s only a few simple lines of code.

How do you achieve the same functionality in Blazor? Like this, obviously:

[Parameter] public ComplexType1 Filters { get; set; }

[Parameter] public string SortColumn { get; set; }

[Parameter] public bool SortDescending { get; set; }

[Parameter] public int PageNumber { get; set; }

[Parameter] public int MaxPages { get; set; }

private ComplexType1 _previousFilters;

private string _previousSortColumn;

private bool _previousSortDescending;

private int _previousPageNumber;

private int _previousMaxPages;

public override async Task OnParametersSetAsync()

{

await base.OnParametersSetAsync();

if (Filters != _previousFilters ||

SortColumn != _previousSortColumn ||

SortDescending != _previousSortDescending ||

PageNumber != _previousPageNumber ||

MaxPages != _previousMaxPages)

{

_previousFilters = Filters;

_previousSortColumn = SortColumn;

_previousSortDescending = SortDescending;

_previousPageNumber = PageNumber;

_previousMaxPages = MaxPages;

await FetchData();

}

}Blazor takes one of the most common use cases in all of web development and makes it a tedious mess. Here are some of the problems with Blazor’s approach:

- It takes way more code to accomplish a simple task. This larger surface area means more room for bugs to hide in.

- It introduces five private fields into the component. Managing this extra state increases cognitivie load and is just asking for subtle state management bugs.

- Nobody ever starts out knowing they need to write this type of code in Blazor. You only discover it after realizing you’re hitting your database ten times more often than necessary and then read this specific section of the docs while troubleshooting the problem.

No Separation of Concerns

In traditional frontend/backend architectures for web apps, you are forced into separating, say, the database logic from the presentation logic. This helps keep your code understandable, maintainable, and flexible. Not in Blazor.

Want to sprinkle some raw database queries into your frontend logic? Go for it, says Blazor. The result is a tangled mess of behavior that is difficult to maintain. Sure, you can avoid this problem manually by creating DTOs or a service layer, or whatever. But the framework itself doesn’t encourage a good architecture.

Blazor Server is a subpar user experience

Blazor Server is a rendering mode of Blazor in which the entire application state lives on the server. Whenever the user interacts with the site, the server renders the updated HTML, compares it to the previous HTML, and only sends the difference between them to the user via a SignalR connection.

First of all, try explaining the phrase “UI diffing over SignalR” to someone who doesn’t know Blazor. That alone should be a signal (no pun intended) that Blazor skews overengineered. But that’s beside the point of this section.

When I first started working with Blazor Server, I expected these constant round trips to the server to feel frustratingly laggy. However, I was pleasantly surprised by how snappy it felt most of the time.

Unfortunately, it only feels snappy if your users have solid internet connections. When their connection is spotty (or when server resources are maxed out), the entire webpage freezes. It is incredibly frustrating when you can’t even open a dropdown menu because your connection is slow!

Too easy to introduce unnecessary state

Most web frameworks these days are “functional” in nature: they take in props and deterministically render HTML based on that state. If you need internal state, you can opt in. I find this functional approach is extremely useful because state is one of the largest sources of complexity and bugs in software. Minimizing state also makes applications easier to reason about, since you don’t have to hold as many concepts in your head at the same time.

Blazor sort of follows the trend of being functional, but mostly doesn’t. Like other frameworks, it has props (a.k.a. “parameters”), but that’s where the similarities end. As a C# framework, Blazor also inherits (no pun intended) much of its design from object oriented programming.

One of the consequences of this design is that Blazor components have mutable state, which can be modified by the component itself or by its parent. This can lead to unexpected behavior and bugs, especially when dealing with asynchronous operations or event handlers. This results in a lot of extra complexity as you are forced to keep all of this state managed and synchronized.

Data binding is incomprehensibly intricate

Data binding is another thing that you would expect your web framework to handle out of the box, right? Wrong. While writing my Blazor app, I ran into an issue where sometimes the characters in an input field would get deleted as I typed them. Turns out it was because I wasn’t using Blazor’s special data binding syntax: @bind. But as I tried to learn the right way to do data binding, I discovered that @bind is a rabbit hole so deep that you will never climb out.

So please don’t ask me to elaborate further on when you’re supposed to use @bind, @bind:get, @bind:set, and when you’re not supposed to use any of them. I will probably cry.

Lacks JavaScript features

Blazor sells itself as a way to write web apps without JavaScript. However, this is a false promise. There are many things Blazor simply cannot do without relying on JavaScript. This means you have to write JavaScript code, expose it to your C# code, and then call it using JSInterop, which complicates what should be a simple task. Essentially, you’re hopping between two languages and troubleshooting in both—doubling the points of failure and the effort needed.

As an example, there is no way to call element.scrollIntoView from Blazor. Instead, you have to write the JavaScript you need, write some way to trigger it from Blazor, and then use JSInterop to hook them together. So now, instead of a JavaScript one-liner, you’ve introduced several new layers of abstraction into your application.

So what’s the alternative?

If Blazor isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, what should you use instead?

The most obvious replacement would be a JavaScript-based framework like React. As shown in the example code above, React doesn’t have the pessimistic re-rendering problem or the multi-language interop problem.

However, for the most complexity-averse among you, I propose a simpler solution: MVC + HTMX.

MVC is the boring, old-school way to write web applications in C#. MVC architecture is much simpler than Blazor’s. With MVC, you don’t have to manage a complex nested hierarchy of components by juggling their lifecycles, parameters, and weird rendering quirks. Instead, all you have to think about is the following cycle:

- A user makes a request.

- MVC passes the request to a controller.

- The controller does some stuff.

- After doing stuff, the controller generates a view (HTML) and sends it to the user.

- The user interacts with the view and sends another request, and the cycle repeats.

That’s it! Simple request/response pattern. So much easier to reason about than nested re-renders.

In case you’re worried about giving up Blazor Components, MVC comes with a ton of helpful features like layouts, tag helpers, partial views, and view components that can help a lot with elimininating duplicated HTML. In my experience, the majority of Razor components do nothing but render static HTML. In these cases, MVC can do the same thing but even more easily, since you don’t have to worry about component lifecycles.

But what about Razor components that need complex functionality? Unfortunately, MVC is inherently less interactive than Blazor. Most of the time, that’s a good thing because it means your web app is simpler. But sometimes you really need more power. One possibility is to combine Blazor and MVC in the same project. This is totally doable, but an even better idea is to avoid Blazor entirely. That’s where HTMX comes in.

HTMX is a library that lets you create powerful single-page-app functionality without sacrificing the simplicity of the HTTP request/response cycle. Think of it like HTML on steroids. As its front page says, it enables you to “build modern user interfaces with the simplicity and power of hypertext.” No JavaScript required.

Here’s a simple example of how MVC + HTMX works. Let’s imagine you have a website with a navbar.

<a href="/page1">Page 1</a>

<a href="/page2">Page 2</a>Now let’s say you don’t want to reload the entire page every time the user clicks a link. Instead, you just want it to just switch out the old page contents with the new page contents.

This is super easy in HTMX.

<a href="/page1" hx-get="/page1">Page 1</a>

<a href="/page2" hx-get="/page2">Page 2</a>The navbar links should have hx-get on them with the same link. The controller action will check if the HX-Trigger header is set, and if so, it only sends a partial view of the page contents, rather than a full view of the entire HTML webpage.

public IActionResult MyPage()

{

if (Request.Headers.ContainsKey("HX-Trigger"))

{

return PartialView("_PageContent");

}

return View();

}The result feels just like a single page app!

Additionally, since the value HX-Trigger is customizable in HTMX, this approach can also be expanded upon by examining the contents of HX-Trigger and returning different sections of the page depending on which element triggered the request.

Experimenting with MVC + HTMX

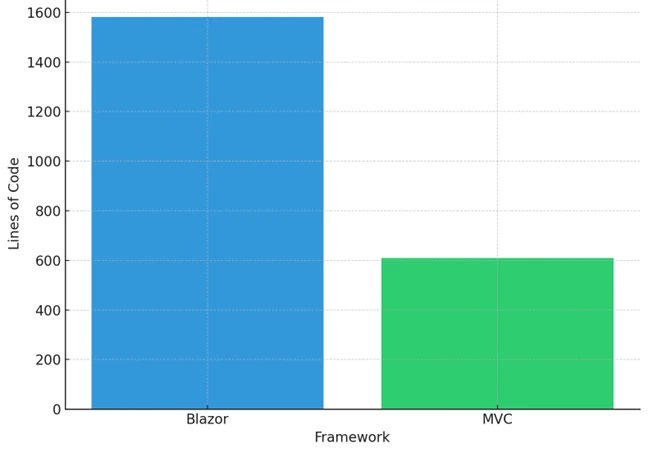

As a proof of concept, I spent two days rewriting a section of an enterprise application from Blazor to MVC + HTMX. The final product was functionally identical to the Blazor version but required 62% less code to implement. This means that not only is it possible to use MVC + HTMX in place of Blazor without any functionality compromises, but the end result will probably be a lot simpler!

The code reduction came mainly from deleting 1) boilerplate parameter passing and 2) component state and lifecycle management. I found that many Razor components were not doing anything particularly complicated and were easy to replace with tag helpers, which reduced the line count significantly.

Granted, lines of code aren’t everything. I’ll take a reasonably verbose, multi-line function over a code-golfed one-liner any day. But in this case, I found the MVC + HTMX code to be both shorter and more readable, flexible, and maintanable. Truly a win in every respect.

Functionality is an asset, but code is a liability

- Ted Dziuba, Taco Bell Programming

Conclusion

So, what’s the moral of the story?

Using Blazor is like travelling to the grocery store in a Saturn V rocket. Sure, it’ll get you there, but it’ll take astronomically more preparation and effort. It requires huge teams before it can take off, and countless things could go wrong. Only 24 people have ever needed a Saturn V rocket. You probably do not need one.

By choosing a simpler solution than Blazor, you will enjoy faster development. Faster development will result in reduced cost of new features and increased responsiveness to customer needs. It will also result in more reliable software, fewer frustrated customers, and (speaking from personal experience) less burnout. At the very least, I hope I’ve kept you from falling into the same pitfalls that I did.

May your day be filled with simple problems and equally simple solutions 🙏